Partners, Harvard Pilgrim Negotiations Underscore Growing Trend

Amid continued merger mania in the U.S. healthcare industry, the news that integrated delivery titan Partners HealthCare is exploring a merger with innovative New England insurer Harvard Pilgrim Health Care stands out.

The deal would not only add to a collection of tie-ups that are blurring the industry’s traditional boundaries — McKinsey & Co. estimates that “vertical integration represented as much as 50 percent of all healthcare deal activity in 2016 and 2017” — but also underscores a more specific trend monitored by Decision Resources Group: integrated delivery networks invading the payer space, displacing traditional insurers, and seizing control over benefit design, drug formulary management, and other key cost controls.

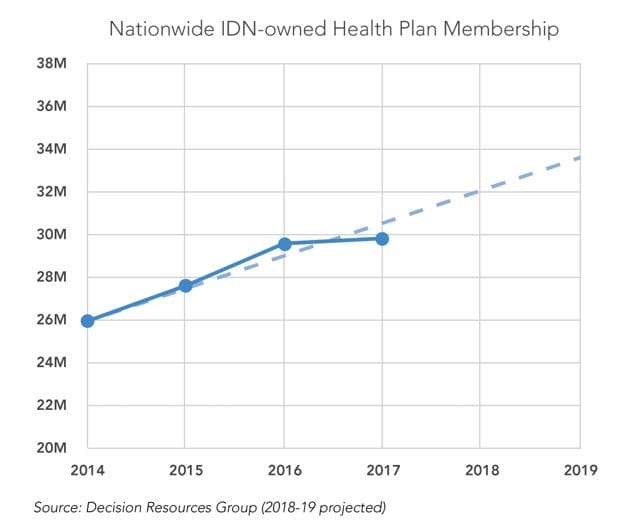

From 2014 to 2016, IDNs added 3.6 million insurance beneficiaries to their rolls, growing owned health plan enrollment at an average annual rate of 7 percent, according to DRG data. That growth cooled from 2016 to 2017, but IDN health plan enrollment still grew by a quarter million lives even as the financial struggles of IDN health plans (including Partners’ Neighborhood Health Plan) made headlines and many provider-led insurers fled from state exchange marketplaces.

The sustained momentum behind payer-provider combinations despite those struggles highlights their long-term strategic value. On a macro level, as government programs and employers increasingly demand outcomes-based financial accountability, it will continue to behoove IDNs to seek whole-dollar ownership around the underlying cost structure of the entire healthcare ecosystem, from bandage prices and physician salaries to provider reimbursements, employer premiums, and beyond.

A deal for Harvard Pilgrim presents additional unique advantages for Boston-based Partners. It presents an opportunity for Partners to grow its business vertically at a time when horizontal health system mergers are under heavy scrutiny in Massachusetts, forcing Partners to look out-of-state for large acquisitions or target smaller Massachusetts providers of specialty care, where there is less angst than in primary care over prices and consolidation. While regulation is more aggressive in Massachusetts than in other states, similar dynamics will increasingly drive IDN vertical integration across the country as anxiety grows over costs, provider consolidation, and the interplay between the two.

Still, a deal that combines the state’s largest, priciest, and most prestigious health system with its second-largest insurer will draw scrutiny from regulators including Massachusetts’ Attorney General, Health Department, and Health Policy Commission.

Expect Partners to argue that pressure to keep insurance premiums low would encourage overall efficiencies at its hospitals, mitigating historic concerns over the market-leading reimbursements Partners commands. Regulators are likely to explore whether Partners could leverage Harvard Pilgrim’s sizeable enrollment to form the foundation of its business and then play hardball with other payers by forcing them to either accept terms favorable to Partners or face members’ ire over losing access to the most reputable hospitals in the state. If the deal goes through, competitors will face pressure to pursue their own consolidations or at least work more closely with other insurers, especially Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, the state’s largest.

In general, payer-provider mergers pose myriad implications for pharmaceutical companies, which must form new relationships and otherwise adapt their market access strategies when control over formularies and overall benefit design shifts from a traditional payer to a payer/provider. What’s more, an IDN’s deepening immersion in insurance operations often is a leading indicator of its readiness and willingness to further catapult traditional insurers from the picture by directly contracting with self-funded employers for the provision of employee health benefits.

But pharma and other players certainly shouldn’t assume an MCO-free future. There are good reasons why providers historically have not done terribly well owning health plans. It’s hard to manage both sides of the traditionally, if not inherently, adversarial relationship between payers and providers, and an IDN that attempts to run a good business on the insurance side will always risk disrupting its traditional operations.

Furthermore, insurers are countering with vertical integrations of their own. Examples include UnitedHealth Group’s acquisition of DaVita Medical Group, as well as the planned combination of Aetna and CVS. There also has been significant growth in what could be a called the “compromise approach” of joint-venture health plans co-owned by IDNs and traditional payers. The joint-venture approach allows IDNs to benefit from the experience and expertise of seasoned insurers, while insurers mitigate a threat by partnering with, rather than competing against, IDNs determined to get in the insurance business one way or another.

Aetna has been particularly active in establishing joint-venture health plans with major IDNs, and has even managed to transform the threat of provider-led health plans into an opportunity by leveraging its joint-venture plans in furtherance of its strategic goal to increase Medicare Advantage enrollment. One component of that strategy is to drive enrollment by offering 4.5- and 5-star rated Medicare Advantage plans in key markets, and health plans tightly aligned with IDNs are more likely to earn the highest Medicare star ratings.

Brandon Gee is a senior analyst at DRG with expertise in Medicare Advantage.

For additional insights, follow Brandon Gee @BSGeeDRG.